A River Runs Through It is Robert Redford’s 1992 period feature about three men and their relationship to God, fly fishing and each other. Seeing as God and fishing are two of the subjects most likely to put me to sleep, I was astonished to find that not only did I stay awake throughout, but that I genuinely enjoyed it.

Much of the credit for this film being watchable has to go Redford. His style is relaxed to the point that it appears effortless, but getting this much authenticity into a film takes serious effort. The cast is excellent, Redford allows them time to find their own cadence, and editors Lynzee Klingman and Robert Estrin cut sympathetically with those rhythms. The way that characters continue living outside the boundaries of the frame is reminiscent of Renoir’s French Can-Can; the shots of Montana rivers and mountains are gorgeous without being pretty; the whole thing is so very sensibly restrained and wise that if I were a more religiously informed person, I’d say for certain that it’s designed to evoke the feeling of the Presbytarianism that crops up throughout the film, but as it is, I can only guess.

The film brings to the screen the memoir of Norman Maclean (Craig Sheffer), which is mostly concerned with his brother Paul (Brad Pitt) as the two of them grow into adulthood in a small Montana town, guided by their minister father (Tom Skerritt) and mother (Brenda Blethyn). It feels as if it takes its time finding a direction as it shows us seemingly unstructured episodes from the boys’ early lives, but as time passes it becomes clear that the film has been sowing the seeds of later events. I’m tempted to write “drama” instead of “events” but this film really isn’t dramatic in the conventional sense. Even the film’s majestic apogee, when Paul is pulled downriver by an enormous fish he has hooked, has an air of restraint that permits you to marvel without feeling sensationalized. Again, this is an achievement of the shot selection, the framings and the pace of the cutting. Throughout the central moment of the film we, as viewer, remain in the position of appreciative bystanders. At no point do we see through Paul’s eyes as he plunges downstream.

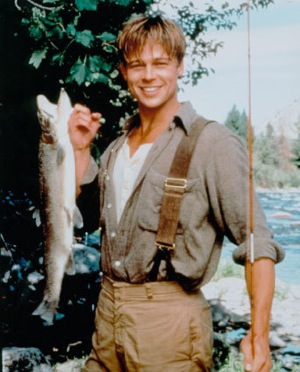

Norman — played totally straight with great dignity be Craig Sheffer — is always the awed observer of the escapade of his confident younger brother, so at home in his Montana surroundings that he is almost a part of the landscape. The way we always see Paul from the outside reinforces the notion of him as a pure force of nature, and this exactly how Brad Pitt plays him: impulsive and unpredictable, from moments of solid tranquillity and concentration to mad whooping and cracked laughter, all the time following his own internal logic.

At times it’s like a religiously and aesthetically filtered East of Eden. The dynamic between the father and the brothers is certainly an echo, and comparison between James Dean in the former and Brad Pitt in the latter is definitely valid, but Eden, which perches on the shoulder of the tearaway brother, is a far more melodramatic and hotheaded film. Watching the two films back to back would be a great lesson in how point of view can thoroughly change a tale’s telling.

What’s heartening is that although A River Runs Through It is exceedingly moral, it doesn’t moralize. The Presbytarianism of the protagonists’ father is a constant, especially in the tone of the framing voice-over from the older Norman, but it is always a considered and thoughtful faith. Paul gambles and misbehaves, waking up in the local jail more than once, but is never judged. It’s a world away from the small-minded hectoring religion that was such a hallmark of Bush’s America.

The way the film builds momentum so patiently, opening up into its tranquil and profound conclusion is quite masterful, and surprisingly moving. I never thought I’d be quite so affected by images of men with rods, line, hooks and dead insects.