My friend Rebecca Marshall’s feature documentary The Forest In Me has its first public UK screening in Lewes on 26th April. It’s a ‘letter to the future’ from Rebecca to her infant son and is told through the interwoven strands of a Siberian hermit woman, a Mars simulation crew in Hawaii, and Rebecca’s son exploring the world.

Turn this man into a coffee shop (or don’t)

I just voted to turn this pensioner into a coffee shop.

My friends Laura and Laurence are Kickstarter funding the postproduction on their Shore Scripts award-winning absurdist comedy He Woke Up to Deflating News. Along with pledging you can also vote on whether to save Michael or uphold the planning permission allowing Bett-a-Boulanger to remodel his insides. Pledge and vote! Or don’t. Your choice.

Swiss embassy: British film retrospective & good cheese

On Monday night I attended a launch event hosted by the Swiss Embassy. Great Expectations, is a retrospective of Postwar British films that will screen at the Locarno film festival later this year. It was particularly interesting to hear curator Ehsan Khoshbakht talk about how he first encountered many of these British films on TV while growing up in post-revolutionary Iran. Apparently during the pre-revolutionary period, when relations with Britain were cordial, a good number of British studio-era pictures were sold to the national broadcaster.

After the revolution, Iranian TV struggled to import new films and they also needed material that would get past the censor – no overt sexuality being a major requirement. British films like It Always Rains on Sunday (1947) struck a delicate balance, alluding to violent crime and dark sexuality without being graphic, and of course there was no need to import them because the physical prints were already in Iranian archives. In some ways the situation is analogous to the way a young Martin Scorsese watched British films on TV in the USA – British films exploited a quirk in the local market (Hollywood studios, with their cinemas in direct competition for audiences with TV, refused to license their films to broadcasters). Given the state of Iran’s international relations and its stance on intellectual property law, it is not clear whether licensing fees were ever paid to British companies for the broadcasting of these films, but what is arguably more important is the role these films played in spreading representations of British society and culture.

There was also a brief appearance from Angela Allen, a legendary script supervisor (but in the immediate Postwar Era her title was “continuity girl”) who worked on a huge number of films from this era, including Carol Reed’s The Third Man (not in the Locarno retrospective for self-imposed curatorial rules: no fantasy, no films set outside mainland UK). I met her briefly in a BECTU event about ten years ago, and it is great to see that she is still as forthright and inspiring today as she was then.

The retrospective features 30+ features and has been compiled with the help of the BFI and the “encyclopaedic knowledge” of Josephine Botting. It will run at the Locarno Film Festival 6-16 August 2025. And the five little Swiss cocktail stick flags I found in my jacket pocket after the event confirm that the Swiss embassy’s cheese offering is as good as you would expect.

Notes on watching a 13 hour film

I spent the majority of my weekend at the ICA watching what seems to be only the third ever screening of Jacques Rivette’s film Out 1 in London since its release 55 years ago in 1970. It is perhaps the least watched of the clutch of films that regularly appear on critics’ “best of” lists. Historically there were a number of obstacles to screening it, not least a run time of just under 13 hours. It is split into eight segments, so it can be viewed with intermissions. Film prints of Out 1 ran at the European standard of 25 frames per second so screenings on North American projectors (which run at 24 frames per second) were half an hour longer still. No subtitled prints of the film were made, so screenings in non-Francophone countries required separate projection of subtitles made by people who were unlikely to have watched the film more than once, and who would have struggled with the frequently overlapping dialogue. Arranging to watch the film with friends, we joked about the provisions we’d need: snacks and water for sure, pillows, iodine tablets, tents, carabiners, as if we were about to climb a mountain of film.

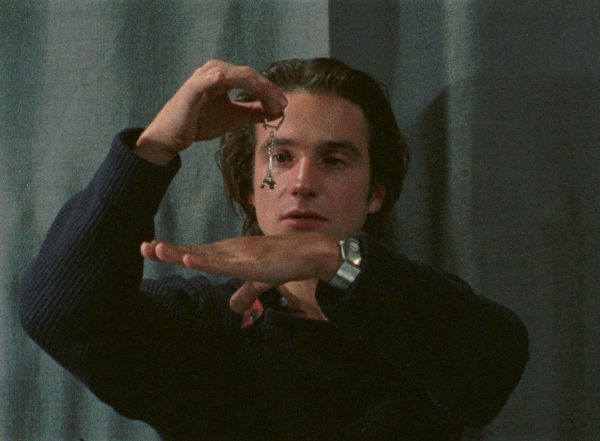

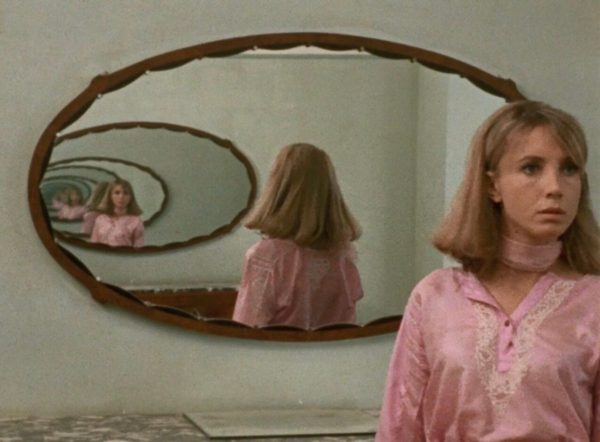

The narrative is made of lightly-edited long-takes of scenes which are mostly improvised. Two different theatre troupes are devising novel approaches to The Seven of Thebes and Prometheus by Aeschylus. The troupes approach their productions almost exclusively through improvisational games and two directors seem to be former romantic partners, now estranged. In parallel to these two ensembles, two ‘outsider’ characters follow solo journeys that occasionally intersect with the actors. A woman seduces men long enough to steal their money until one day she accidentally steals some intriguing and incriminating letters that point towards a conspiracy, and a young man (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud) receives cryptic notes that send him on a Quixotic investigation into a secret society called The Thirteen named for an Honoré de Balzac novel. The first three hours are impressionistic and introduce most (but not all) of the principal characters, and the first act break seems to arrive in the fourth hour.

The pacing and length and looseness of the scenes make the viewing experience particpatory – a particular primal grunt, a foot shoved into the mouth of an actor during a physical improvisation, the repetition of a gag to absurdist degrees, all become stimuli for speculation. Just as the actors attempt to collaboratively devise their productions, the viewer becomes a participant in a one-sided game of ‘yes, and…’, that involves picking up the performers’ loose ends and attempting to weave them into a fabric of meaning. This is different from the process of piecing together a more conventional ‘closed’ filmic narrative that seeks to minimize ambiguity because there is no guarantee that the elements of the dialogue and mise-en-scène really do mesh together. The closest the film comes to explaining itself is when two of the more ‘in the know’ characters hypothesize about the thoughts and actions of a third character who has never appeared on screen. The cumulative experience is similar to pareidolia – the attempt to impose a meaningful interpretation on something nebulous, such as looking at a cloud and seeing the shape of an alligator, or seeing mind control chemicals in aeroplane vapour trails.

Rivette used this narrative strategy in other films, such at Le Pont du Nord (1981) and David Lynch draws from a similar well for Twin Peaks, particularly in season three (2017). It is freewheeling, strange, and defiantly uncommercial. The whole thirteen hours of narrative were shot over a similar number of days to a regular 90 minute film, and many of the scenes seem to have been captured in one take. Child extras look down the barrel of the lens in interiors, and during exterior shots everyone stares at Jean-Pierre Léaud, who was one of the most recognisable faces in France at the time. A gaggle of young boys follow him down the street during one of his stranger monologues. Actors make abortive attempts to light cigarettes, fluff their lines or accidentally block narrative motion with a ‘no’ rather than a ‘yes, and…’, sending improvisations into meandering loops. Lighting is frequently rudimentary, boom shadows fall into shot, cuts to black disguise what would otherwise be awkward jump cuts. It is self-indulgent, messy, frequently confusing (two characters go by multiple names, depending on who they are with), and the few bursts of violent action are cheaply and unconvincingly staged. And yet despite these flaws it holds the attention like a hypnotist’s pendulum – the consciousness drifts but remains somewhat anchored.

In a strange way Out 1 predicts the ‘episodic’ storytelling that would come to prominence in the streaming age, in which the individual arc of a single episode is subordinated to the arc of the entire work. In other ways it feels like an initiation, a rite of passage on the path of committed cinephilia. Even the title positions it as a filmmaker’s film. Rivette only ever called the full film Out 1. A four-and-a-half hour cut was made of the same basic narrative, which came to be known as Out 1: Spectre. “Noli me tangere” was a note stuck to the cans containing Rivette’s preferred 13 hour cut. The phrase is latin for “do not touch me,” and it is what Jesus said to Mary Magdalene when she recognised him after his resurrection. And so we have the epic director’s cut as a holy artefact, the ultimate sanctified relic of auteurism. For the casual cinemagoer it’s little more than a pointless diversion, but for the a committed believer in the cinema Out 1 is a pilgrimage.

Achievement unlocked: PhD

On the morning of Wednesday 24th August I was hooded by the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Kent along with eight other PhD graduands and a host of BA, MA, and PGDip recipients. The title of the thesis, which was read in full just before I received my degree is Mythical Middle England: Illuminating the Aesthetic Potential of English Non-Places Through Narrative Cinema. It has been a long process, and one which has changed the way I think about my topic of study, the way I approach my work and my sense of self. I don’t feel like recounting much about the thesis itself in this post right now, but I do want to cite the acknowledgements publicly here.

I have many people to thank for helping me reach this stage in the PhD, and my continuing artistic voyage into deepest Middle England: firstly Lavinia Brydon for her unflagging guidance and support throughout bewildering changes in global and personal circumstances, Frances Kamm and Murray Smith for stepping in towards the end of the process to help me over the line, Richard Misek and Mattias Frey for their guidance at key points in the earlier stages, Lawrence Jackson for film folklore tips, and Angela Whiffen for interpreting university administrative liturgy into vernacular speech. The time you have all given me is precious.

Resources are also useful, especially for PAR projects, and I would like to thank the School of Arts and the University of Kent for the Vice-Chancellor’s Scholarship award for the financial support.

Also within the field of academia, I would like to thank Dr. Jane Adams for our conversations about healing with water and Dr. Catherine Robson for encouraging my academic and teaching career more generally.

Outside the university, a great many people have given their time and their skills to make the creative output of this project possible. I acknowledge that contributions of cast, crew, and documentary subjects in the credits of the films but I cannot thank cinematographer Alexandru Grigoras, editor Svitlana Topor, and script editor Margaret Glover enough times for their contributions to the films, and for being the kind of collaborators who save me from bad filmmaking decisions.

The cartographical parts of this study would have been impossible without the help of Beth Manghi, whose GIS coding helped me plot the settings of British films.

This written thesis and the two films are all dedicated to the memory of Dr. John Harcup, who was my grandfather’s GP, and who later became my documentary subject, historical adviser to the short film Water Cure, a supporter, and a friend. It is rare to meet someone who blends a natural authority and the power to make things happen with curiosity and good humoured humility. He is missed.

Immediate family have also been crucial. David and Leonie Creighton for helping with outlandish requests, storage, and places to sleep, Duncan Graham and my sisters Caitlin and Rhianon Graham for keeping me moving both physically and psychically, and of course Courtney Hopf for more than twenty years of shared growth, enduring the demands of my muse, constant notes and reassurance and, yes, proofreading.

In Buñuel’s footsteps

I’m going to be in Toledo all next week attending the Conecta European TV networking event, and sticking around a couple of days afterwards for a little city break which will probably involve bicycles at some point.

When I mentioned to my friend Svitlana that I was going there, she told me the city was beloved by Luis Buñuel. A little digging, and it turns out before the Spanish Civil War, when they were all alive and on speaking terms, Buñuel, Dalí and Lorca visited Toledo and, “fascinated by the mysterious air it gave off,” were moved to invent their own semi-satirical religious order/artists collective, the Order of Toledo. More about it in this article by Roberto Majano.

The principle activity of the order was “to wander in search of personal adventures” and the induction ceremony was to be stranded alone in the darkness of Toldeo at the toll of the 1am bell. This reads to me very much like a precursor to the Situationist activity of dériving around Paris. Perhaps Guy Debord drew inspiration from Buñuel?

Bonus anecdote: Buñuel hired a sex worker in the city, not apparently for sex, but in order to hypnotise her, because surrealist research doesn’t have to answer to ethics committees.

MiniDisc Rediscovery

I just dug out my venerable MiniDisc player out and hooked it up to my amp to play some tunes that I don’t have on MP3 or CD. I love MiniDiscs – they never went mainstream, so there’s something about them that just feels sci-fi, which probably explains why they appear in The Matrix and Strange Days.

One day I will own a LaserDisc player, which I will only be able to use to play Bladerunner, and it will be absolutely worth it.

“Stardom” by Denys Arcand

At the moment I’m checking out films about models and photographers. It’s part of my research for the short I’m developing.

Denys Arcand’s film Stardom (2000) is a high-pace satire. Tina Menzhal (Jessica Paré) is plucked from small-town Canadian obscurity and is launched into a whirlwind of money, fame and failed romances. Starting with cable access station footage, the film makers show Tina through the lenses of the media circus that gathers around her. There’s the fashion reporter with her video camera and aggressive style; there’s the genuine artist and camera nerd photographer who follows her, shooting black and white 16mm with an Aaton on his shoulder; there are news reports and chat shows. What we don’t see is Tina on her own terms. She is subject to constant attention, the invasion of her privacy, and endless demands. Everyone wants a piece of her. Men (including great turns from Dan Aykroyd and Frank Langhella) ruin themselves on what they think is her behalf, without ever figuring her out.

The event that ends the hysteria and concludes the film leaves a little to be desired. Awarding a prize to a ruggedly handsome doctor who has won a marathon, Tina falls in love. The notion that the key to happiness is a bun in the oven given to her by a stand-up guy from her hometown is the kind of simple and regressive formulation that the film has been skewering for the last hour and a half. But up until that point it’s been such a hell of a ride that you’re willing to forgive Stardom its mis-step.

The Library of Burned Books Nears Completion

Alasdair and I had an amazing morning grading “The Library of Burned Books” with Maria at Narduzzo Too on Monday. Now all we need to do is have the sound mixed, and we will be ready to launch the film on the festival circuit. I’ll post some stills from the final graded version soon. Thanks also to the good folks at diRoom for their work on the previous cut of the film.

Dune

David Lynch was thrust into development of Dune too early in his career, it seems. The producers’ idea was to profit on the success of Star Wars by creating another sci-fantasy epic, but a standard length feature film is not a big enough container for Dune, with all its plotting, counter-plotting and Messiah-creation.

I’ve now seen both the original theatrical release, on which Lynch has the director’s credit, and the TV edit, which is attributed to Alan Smithee. It was the Smithee version that I just watched. The producers, showing an absolutely dreadful grasp of the possibilities of film, front-load about three hundred years of exposition using a dull voiceover and a bunch of hastily assembled paintings, some of which recur multiple times. The aim, apparently, was to save time in order to cut to the action quicker, but seeing as it takes about ten minutes to outline everything, it is deathly, deathly boring.

I think most people who are aware of Dune know that Lynch had to struggle to trim his rough cut from about four hours down to about two and a half, and that as a result the story is unclear and under-motivated. It feels as if a missed opportunity flies by every five minutes, but despite this, there is still something interesting buried in the narrative rubble. Much of the time the production design is evocative and hints at a society that exists beyond the screen, and there is something that sticks with you in the dream sequences — which is what you’d expect from Lynch’s direction. Performances from Kyle MacLachlan, Max von Sydow and Patrick Stewart are commendable, and there’s an almost unparalleled moment of male objectification when Sting steps out of a futuristic shower clad only in a large white nappy while his uncle, an evil duke, coos and drools over him.

Probably the best way for Dune to be brought to the big screen is as a trilogy, pitched somewhere between the original Star Wars movies and the Lord of the Rings. One would hope the latest crew to attempt to make it would dig Lynch’s early four-hour rough cut out of the archives as part of their research, because as imperfect as it is, there is something worth salvaging.

Quote from number9dream

The missus is re-reading David Mitchell’s number9dream for the dissertation. Every now and then she reads a bit aloud for me.

I watched for a while longer. Not much happens in Paris Texas.

“Sort of slow, isn’t it?”

Buntaro licks his hand.

“This, lad, is an existentialist classic. Man with no memory meets woman with huge hooters.”

I really enjoy days when I write and she reads.

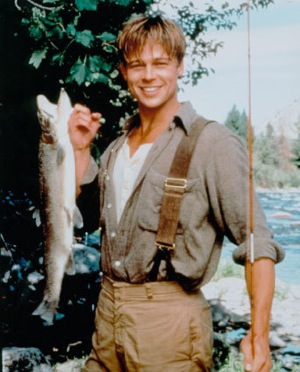

A River Runs Through It

A River Runs Through It is Robert Redford’s 1992 period feature about three men and their relationship to God, fly fishing and each other. Seeing as God and fishing are two of the subjects most likely to put me to sleep, I was astonished to find that not only did I stay awake throughout, but that I genuinely enjoyed it.

Much of the credit for this film being watchable has to go Redford. His style is relaxed to the point that it appears effortless, but getting this much authenticity into a film takes serious effort. The cast is excellent, Redford allows them time to find their own cadence, and editors Lynzee Klingman and Robert Estrin cut sympathetically with those rhythms. The way that characters continue living outside the boundaries of the frame is reminiscent of Renoir’s French Can-Can; the shots of Montana rivers and mountains are gorgeous without being pretty; the whole thing is so very sensibly restrained and wise that if I were a more religiously informed person, I’d say for certain that it’s designed to evoke the feeling of the Presbytarianism that crops up throughout the film, but as it is, I can only guess.

Boston’s on the Ball

You know that festival organizers are on the ball when they send each filmmaker an individual email with a link to where to buy tickets for their film’s screening. Thanks, Boston!

Click here to buy tickets for “Julie, Julie” at the Independent Film Festival, Boston.

Lakeview Terrace

Warning: spoilers after the jump.

It feels as if Samuel L. Jackson has spent the last few years sliding into self-parody in formulaic big-budget films, so I was keen to see him exercise his craft in Lakeview Terrace, an exploitative little thriller set in the LA suburbs. Likewise with its director, Neil LaBute, who caused a stir fifteen years ago with misanthropic indie movies like In the Company of Men, but whose last credit before this was a nasty-looking remake of The Wicker Man, which I refused to see on principle. The idea of both men reminding us why they’re worth watching by getting back to basics is very appealing.

Lakeview Terrace pushes on the pressure points of race relations. Young bi-racial, college educated, hybrid-driving couple Lisa and Chris Mattson (Kerry Washington and Patrick Wilson) have just moved from Oakland to the LA suburbs and are celebrating their freedom from the supportive but smothering influence of parents. Abel Turner (Samuel Jackson) is their cop neighbour, a friendly and authoritative lawman who works a tough beat in the inner-city and spends his off-duty time policing their suburban neighbourhood for fun. But of course, in films like this suburbia is never what it seems on the surface. The threat to normality is present from the very beginning, as Lisa and Chris check the reports on the summer wildfires to be sure that their new home is safe.

“Julie, Julie” promotional website now live

I’ve spent this week up to my armpits in jpegs, pngs, html, css, mp4s and H.264, and this is the result. Please, friends, take a look and send me screenshots and news of how the site works for you. I’m especially keen to find out how it works on Windows computers running Internet Explorer, because as a Mac user, I am sheltered from the vagaries of Microsoft’s browser. For all I know it might display in cyrillic on Windows.

Notice how the “Screenings” page of the website lists two festivals! Hopefully the first two of many.

Film Council Launches Film Search Website

The Film Council’s new service, Find Any Film looks like it could turn into something rather good. At the moment it can tell you the nearest cinema that’s showing a film of your choice. This has been a feature of www.imdb.com in America for years now, but is apparently a first for the UK. It can also tell you if the film you’re looking for is due on TV, or is available on disc or for download.

More features are due to be added, which is necessary if it is to become more than just a good looking UK-specific imdb clone in order to succeed.

It would be great if they could sign a deal with the BFI to carry reviews and/or synopses from Sight & Sound, but I’m not sure how they could do so without killing Sight and Sound’s circulation. Anyhow, I’m looking forward to using it properly when I return to the UK in June. Let’s hope it helps small exhibitors attract larger audiences and promotes small, interesting and British films.

O Lucky Man!

A seventies filmic retelling of Candide by director Lindsay Anderson, writer David Sherwin and star Malcolm McDowell, O Lucky Man! is a rare example of the picaresque in cinema. Starting as a coffee salesman, McDowell’s Mick Travis (the same name, but perhaps not quite the same character as he played in If….) journeys through Britain’s regions, classes and professions veering from cynical capitalist to idealistic altruist. Finally he learns that the best one can hope for is to not die like a dog, and that even if our best shot at understanding the variety and confusion of the world is through the imprecision and contariness of art, at least we can turn our attempts into entertainment.

McDowell is ever-present as a boyish, charming everyman, his strange open face and piercing blue eyes the perfect vehicle for a character who can pass through corruption, torture and victimisation and still emerge fresh and apparently innocent on the other side. Around him an ensemble cast, including Arthur Lowe, Ralph Richardson, Mona Washburn and Helen Mirren, recur in multiple roles, bringing the film’s artificiality to the fore.

Two Lovers

This is a low-key romantic drama starring Joaquin Phoenix and Gwyneth Paltrow, with a couple of good supporting turns from Isabella Rossellini and Elias Koteas. I expected a solid piece of drama, and that is what we saw. Joaquin Phoenix plays Leonard Kraditor, a late twenty-something living in Brighton Beach, a far flung New York neighbourhood. Suffering from bi-polar disorder and low self belief after his planned marriage is scuppered by his future in-laws, he has returned to living with his parents and working in the family business as he tries to put his life back together. His father, Reuben, owns a launderette which he plans to merge with one owned by Mr. Cohen, another Jewish businessman. The two families meet for dinner at the Kraditor’s place, and it becomes somewhat clumsily obvious that the two fathers are planning to cement the business merger with marriage. Sandra Cohen, played by Vinessa Shaw, appears to be a pleasant and unremarkable woman, and as much out of a sense of obligation as anything else, Leonard plays along with the game set up for him by his parents until he a chance meeting with a beautiful and engaging neighbour, Michelle, played by Gwyneth Paltrow.

Two Lovers is a well-made movie, and plots its course from one event to another in a steady fashion, but at no point does it do anything exciting or inventive. It’s set in a humdrum part of New York, and the filmmakers evoke that mundanity precisely. Much of the movie consists of close and medium shots, the interiors of apartments and launderettes, and little attempt is made to find beauty in these spaces. It seems that Leonard harbours some ambitions in the direction of photography, which would perhaps offer him some escape from his feelings of entrapment, but the only photos of his we see are head-on shots of local businesses. At no point do either the viewer or Leonard have any respite from the everyday, and the everyday is presented as being dreary. The tone of the film is inflected by Leonard’s subjectivity, but only the sad part. It seems the filmmakers missed a trick by not investigating the possibility of seeing the world through Leonard’s eyes when he’s “up.”

Let the Right One In

Or, in the original Swedish, Låt den rätte komma in is the sweet and troubling coming-of-age story of Oskar, a young boy who finds the confidence to fight bullies and assert his place in the world when he falls in love with the girl next door. However, as he gets closer to Eli he realises there might be something sinister about her. Of course there is: she’s a vampire.

Last month I caught up with Twilight, the yardstick by which teenage vampire movies are currently measured. The American vampire movie had plenty of thrills and spills, but it rarely strayed from the established good-girl-meets-dangerous-guy formula – a bit like Dirty Dancing with lots of white goth makeup and little emotional honesty. Let the Right One In is quite different. The tone is measured and, while it’s not as intentionally halting or sparse as Roy Andersson’s Songs from the Second Floor or Aki Kaurismäki’s The Man Without a Past, there’s a similar buttoned-down nihilism underpinning proceedings.

Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired

A fascinating documentary about the trial of superstar film director Roman Polanski on a variety of charges of sexual misconduct with a thirteen-year-old girl. It’s very sympathetic to Polanski, but it should be noted that the director/producer is a woman, and doesn’t ignore the suffering of the victim. The worst aspect of the entire case was the conduct of the judge, Laurence J. Rittenband, who courted the press throughout and changed the sentence several times in order to appear to be hard enough in front of the press. He was so bad that even the lawyer in charge of the prosecution thinks Polanski was hard done by.

36 Quai des Orfèvres

Daniel Auteuil and Gerard Depardieu pay the bills in this stylish French police suspense movie. Their collective star power almost diverts from the fact that they’ve both eaten too much foie gras to play active, hard-edged policemen. There’s plenty of double-dealing and blurred moral boundaries, but the script sets up the dead bodies a little too obviously. Will there ever be a cop movie in which the officer who’s on the verge of retirement actually lives into his dotage? Or one in which the pretty wife of the hero doesn’t have a torrid time?

Even though this is pretty standard fare for these two stars, it’s still tighter and more dramatically interesting than similar Hollywood genre flicks. And given that 36 Quai des Orfèvres is the French equivalent of Scotland Yard, the filmmakers suggest that corruption and shady dealings are endemic even in the upper echelons of French law enforcement. It’s a smart movie, and delivers exactly the kind of thrills you expect. The pairing of Auteuil and Depardieu is clearly a French attempt to emulate the De Niro & Pacino pairing of Heat or Righteous Kill, and although I understand exactly why they cast it that way I think the movie would have been dramatically stronger with a pair of leaner, hungrier actors.

If you live in a world in which you have a choice between this and, say, Righteous Kill, go for the French movie, you won’t regret it.

Highlander

Was I half-asleep or was it never adequately explained why “There can only be one?”

Highlander was a complete pile of nonsense, with a barely anglophone Belgian, Christopher Lambert, playing a Scotsman and Sean Connery playing a Spanish-Egyptian swordfighting dandy. Lots of latent sadomasochistic homosexuality and some utterly unreal lighting, including gutter-level strobe lights.

It was showing on ITV, so there were frequent advert breaks, but oddly there were no real adverts, just solicitations to watch other programmes on ITV. Has the credit crunch killed TV advertising?

Cinéma Utopia

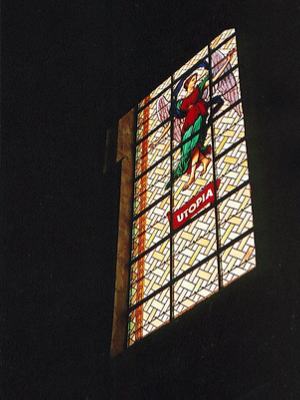

The other night C and I made a thorough investigation of one of Bordeaux’s cultural gems. Cinéma Utopia in the Saint Pierre district, at the heart of the historic centre ville is a five screen arthouse cinema housed in a converted church. The screen we sat in was small but adequate and the area around and underneath the screen was painted to resemble an altar with candles to each side. This irreverence is played out elsewhere in the building too. Some of the original stained glass windows have been modified to include the Utopia’s logo.

For a dedicated cinephile, the Utopia is aptly named. The films are not preceded by commercials or trailers. You sit and wait, the lights go out, people fall silent and the movie starts, just like that. It’s refreshingly pure to experience cinema treated with the same respect as theatre. During the movie everyone stays totally silent. There is no popcorn munching, (you can’t buy popcorn at the Utopia) nobody answers their phone and nobody issues whispered pleas for explication to their friends. The film we saw was Sidney Lumet’s The Verdict, from 1982, an original print in fine shape. There was a little dirt around the beginning and end of each reel and a significant amount on the tail of the film, which is to be expected. The colours had faded a little, but Paul Newman’s eyes were still startlingly blue. At the end of the film the house lights stayed down until the very end of the credits so you either watch until the very end or bumble about like an idiot in the pitch black.

The Utopia has a café and it’s the real French deal. Like I wrote earlier, there is no popcorn. There is no candy, either. There is an abundance of coffee, and a decent selection of beer, wine and pastries. Some wholesome and tasty meals come out of the kitchen. There is free wi-fi, but the place isn’t crammed with people bathing in the blue light of their laptop screens. The café has a couple of terraces of tables on the square outside, and I think it must bring in more money than the cinema itself. A full-price ticket for the Utopia is €6, and an abonnement (subscription) of 10 admissions costs €45. The multiplexes in town charge around €7,50. In the month of September they showed 36 different films, from a wide selection of countries and from different eras. Right now you can see the prizewinners from Cannes alongside retrospectives of great movies from the archives. In the coming month the selection of classic Hollywood movies includes Siodmak’s The Killers, Kazan’s East of Eden and Hawks’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. There is even philosophical and political graffiti in the toilets. The Utopia really lives up to its name.

It was spookily coincidental that the film we watched that night was The Verdict, in which a lawyer, whose idealism and naivety have cost him a comfortable job and his self-respect, takes a medical malpractice case to court, though it would be easier to settle, in order to do the right thing. It’s a classic tale of the little guy versus the big man, and yet Paul Newman in the title role and the direction of Sidney Lumet are create an emotional gravity that is modest, thoughtful and compelling in a manner seldom seen on screen in recent years. I hate to come across all curmudgeonly and say “They don’t make them like that any more,” but they really don’t.

On the way back from the cinema C and I were admiring Paul Newman as both a great performer, a genuinely good and philanthropic guy, and a good example of an American liberal. There are more films playing at the Utopia that benefited from Newman’s involvement, including one that he directed. I’m planning to make the most of the opportunity to see them. Having seen some of his best work the night before made the announcement of his death a little sadder for us. Damn, he was good.

I Drink Your Milkshake

This weekend has been my first time off from jobs and movie stuff for about two, maybe three months. After ignoring most of the Superbowl, I took Courtney to see There Will Be Blood. Within the first minute she whispered in my ear “I really notice cinematography now.” At that moment I think my heart skipped a beat.