I spent the majority of my weekend at the ICA watching what seems to be only the third ever screening of Jacques Rivette’s film Out 1 in London since its release 55 years ago in 1970. It is perhaps the least watched of the clutch of films that regularly appear on critics’ “best of” lists. Historically there were a number of obstacles to screening it, not least a run time of just under 13 hours. It is split into eight segments, so it can be viewed with intermissions. Film prints of Out 1 ran at the European standard of 25 frames per second so screenings on North American projectors (which run at 24 frames per second) were half an hour longer still. No subtitled prints of the film were made, so screenings in non-Francophone countries required separate projection of subtitles made by people who were unlikely to have watched the film more than once, and who would have struggled with the frequently overlapping dialogue. Arranging to watch the film with friends, we joked about the provisions we’d need: snacks and water for sure, pillows, iodine tablets, tents, carabiners, as if we were about to climb a mountain of film.

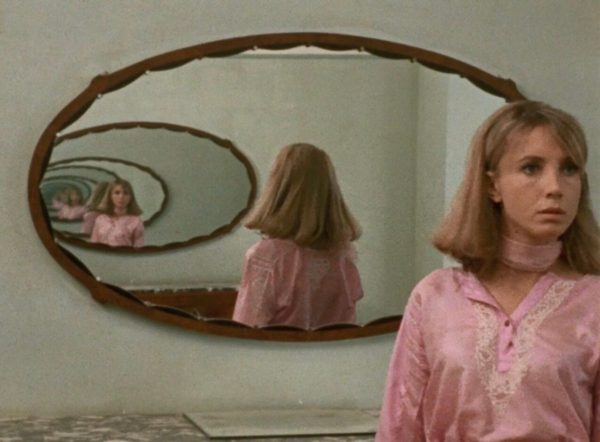

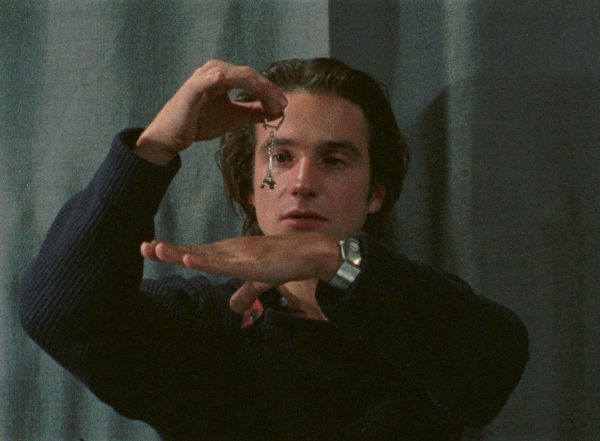

The narrative is made of lightly-edited long-takes of scenes which are mostly improvised. Two different theatre troupes are devising novel approaches to The Seven of Thebes and Prometheus by Aeschylus. The troupes approach their productions almost exclusively through improvisational games and two directors seem to be former romantic partners, now estranged. In parallel to these two ensembles, two ‘outsider’ characters follow solo journeys that occasionally intersect with the actors. A woman seduces men long enough to steal their money until one day she accidentally steals some intriguing and incriminating letters that point towards a conspiracy, and a young man (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud) receives cryptic notes that send him on a Quixotic investigation into a secret society called The Thirteen named for an Honoré de Balzac novel. The first three hours are impressionistic and introduce most (but not all) of the principal characters, and the first act break seems to arrive in the fourth hour.

The pacing and length and looseness of the scenes make the viewing experience particpatory – a particular primal grunt, a foot shoved into the mouth of an actor during a physical improvisation, the repetition of a gag to absurdist degrees, all become stimuli for speculation. Just as the actors attempt to collaboratively devise their productions, the viewer becomes a participant in a one-sided game of ‘yes, and…’, that involves picking up the performers’ loose ends and attempting to weave them into a fabric of meaning. This is different from the process of piecing together a more conventional ‘closed’ filmic narrative that seeks to minimize ambiguity because there is no guarantee that the elements of the dialogue and mise-en-scène really do mesh together. The closest the film comes to explaining itself is when two of the more ‘in the know’ characters hypothesize about the thoughts and actions of a third character who has never appeared on screen. The cumulative experience is similar to pareidolia – the attempt to impose a meaningful interpretation on something nebulous, such as looking at a cloud and seeing the shape of an alligator, or seeing mind control chemicals in aeroplane vapour trails.

Rivette used this narrative strategy in other films, such at Le Pont du Nord (1981) and David Lynch draws from a similar well for Twin Peaks, particularly in season three (2017). It is freewheeling, strange, and defiantly uncommercial. The whole thirteen hours of narrative were shot over a similar number of days to a regular 90 minute film, and many of the scenes seem to have been captured in one take. Child extras look down the barrel of the lens in interiors, and during exterior shots everyone stares at Jean-Pierre Léaud, who was one of the most recognisable faces in France at the time. A gaggle of young boys follow him down the street during one of his stranger monologues. Actors make abortive attempts to light cigarettes, fluff their lines or accidentally block narrative motion with a ‘no’ rather than a ‘yes, and…’, sending improvisations into meandering loops. Lighting is frequently rudimentary, boom shadows fall into shot, cuts to black disguise what would otherwise be awkward jump cuts. It is self-indulgent, messy, frequently confusing (two characters go by multiple names, depending on who they are with), and the few bursts of violent action are cheaply and unconvincingly staged. And yet despite these flaws it holds the attention like a hypnotist’s pendulum – the consciousness drifts but remains somewhat anchored.

In a strange way Out 1 predicts the ‘episodic’ storytelling that would come to prominence in the streaming age, in which the individual arc of a single episode is subordinated to the arc of the entire work. In other ways it feels like an initiation, a rite of passage on the path of committed cinephilia. Even the title positions it as a filmmaker’s film. Rivette only ever called the full film Out 1. A four-and-a-half hour cut was made of the same basic narrative, which came to be known as Out 1: Spectre. “Noli me tangere” was a note stuck to the cans containing Rivette’s preferred 13 hour cut. The phrase is latin for “do not touch me,” and it is what Jesus said to Mary Magdalene when she recognised him after his resurrection. And so we have the epic director’s cut as a holy artefact, the ultimate sanctified relic of auteurism. For the casual cinemagoer it’s little more than a pointless diversion, but for the a committed believer in the cinema Out 1 is a pilgrimage.